This post is intended to give a history of the dispute over Santa Monica Airport (SMO) ownership between the City and the FAA as well as of the mounting opposition to the airport from the impacted residents in the surrounds. We will not give a full history of SMO itself and the issues surrounding it, for that you can watch CASMAT’s March 2013 video which can be found here.

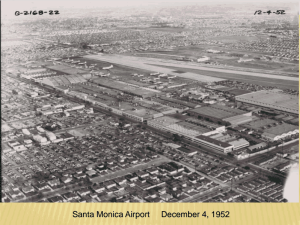

In the late 1950’s, Douglas began development of the DC-8, a 4-engine jet-powered airliner. By 1967 a total of 59 claims regarding jet activity were brought by nearby residents. The company proposed further lengthening the current SMO runway to accommodate the new aircraft and acquiring additional land to build new corporate offices. This would have required the bulldozing of additional residential areas; this had already happened once in 1941 when US Government changed the original two shorter runways in an X configuration to a single longer runway for wartime use (so expanding the airport to 227 acres). The City of Santa Monica declined the request.

In the late 1950’s, Douglas began development of the DC-8, a 4-engine jet-powered airliner. By 1967 a total of 59 claims regarding jet activity were brought by nearby residents. The company proposed further lengthening the current SMO runway to accommodate the new aircraft and acquiring additional land to build new corporate offices. This would have required the bulldozing of additional residential areas; this had already happened once in 1941 when US Government changed the original two shorter runways in an X configuration to a single longer runway for wartime use (so expanding the airport to 227 acres). The City of Santa Monica declined the request.

In 1968, the City in an attempt to shield itself from litigation proposed a jet curfew, this was challenged in the court of appeals, but eventually upheld. Subsequently, Douglas shifted the manufacturing of jet aircraft to Long Beach Airport and completed its relocation to Long Beach in 1975. By 1977, the Douglas plant, which had at one time been the largest factory in the world (employing 44,000 workers operating in shifts), became a vacant dirt lot. In that same year, the City’s noise ordinances (introduced in 1975) were challenged but upheld in Federal District Court, however, the jet ban was held to be unconstitutional.

With Douglas gone, the jet issue for a while became less important, but the City was now left with a huge, expensive, and largely unused block of land. After conducting an economic analysis in 1980, the City determined that the airport was not economically viable and decided to close it. Once again the City is challenged and the case is litigated in both state and federal courts where the City eventually prevails. In June 1981, the Council adopted resolution #6296 declaring its intention to close the Airport as soon as possible. The FAA and the Santa Monica Airport Association (Airport Association) file another suit challenging. In 1982 the parties reach an agreement to conditionally dismiss.

In 1984 the highly charged dispute with the FAA is resolved through the Santa Monica Airport Agreement, which obligates the City to operate the Airport through 2015 but recognizes the City’s authority to mitigate aircraft impacts through the existing noise limit, curfew, helicopter training ban, and pattern flying restrictions.

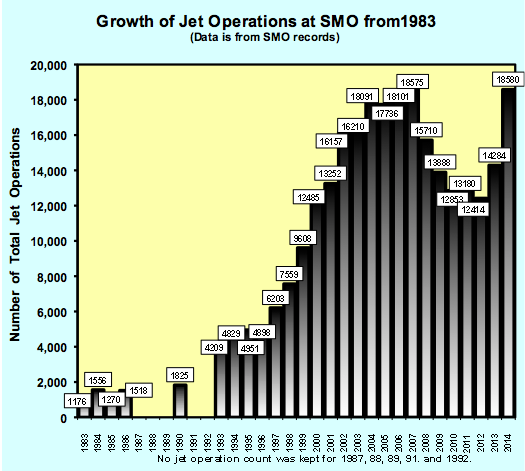

In the mid 1990’s, With the booming economy, new development on the Westside, and the advent of fractional ownership of aircraft, jet operations increase from about 5 to 6 per day to around 15 per day. Larger, faster jets in Categories C and D constitute an increasing percentage of jet operations. Opposition to the airport begins to rise as a result.

In 1998, The Airport Association files a Federal Administrative (Part 16) complaint with the FAA alleging multiple breaches of the 1984 Agreement. The FAA eventually issues a determination in favor of the City, and the complainant Association seeks review by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals; ultimately, the case is dismissed in 2006 when new leases are entered into with two limited FBOs. Again in 1999 the Airport Association files a State court action raising issues similar to the prior Part 16 complaint. Several years later, the Los Angeles County Superior Court rules in favor of the City on 28 of 29 issues; and eventually, the California Court of Appeals dismisses the entire action on grounds that the Association lacked standing to enforce the 1984 Airport Agreement between the City and the Federal Government. The dismissal was subsequently affirmed by the California Supreme Court.

Also in 1999, Los Angeles neighbors file a lawsuit against the City in State court (Cole v. City) seeking damages and injunctive relief claiming that aircraft operations at the Airport created liability for the City based on inverse condemnation, adverse health impacts, and nuisance. Eventually, following a lengthy trial, the Court dismisses all the inverse condemnation claims and most of the other claims. Three plaintiffs receive minimal damage awards, but the airport is officially declared to be a ‘public nuisance’. That designation still stands today.

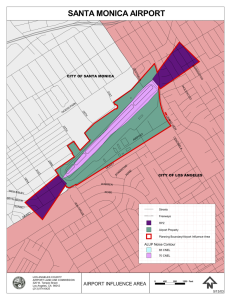

In 2000 to 2002, the economy booms, the FAA approves fractional (shared) ownership of jets, and the Airport fleet continues to evolve with total jet operations increasing to about 30 to 40 per day. The City initiates a review and study of the Airport’s runways and other operational design features to determine their compatibility with the changing fleet. The study concludes, among other things, that the more demanding Category C&D aircraft now account for 5% of jet operations, that the critical design aircraft using the Airport is now the D-II aircraft (the Gulfstream IV), and that the Airport (which has no runway safety areas), lacks sufficient runway safety areas per current FAA design guidelines for all aircraft approach categories. Additionally, the review concludes that the Airport’s geographical layout and the close proximity of runway ends to roadways and residential neighborhoods effectively preclude the construction of the traditional graded runway safety areas. Therefore, the report suggests designating runway safety areas by displacing the landing thresholds 300′ at both ends of the runway to create safety areas consistent with the Airport’s B-II designation by effectively shortening the usable runway; however this would leave the usable runway too short for C&D aircraft.

In 2000 to 2002, the economy booms, the FAA approves fractional (shared) ownership of jets, and the Airport fleet continues to evolve with total jet operations increasing to about 30 to 40 per day. The City initiates a review and study of the Airport’s runways and other operational design features to determine their compatibility with the changing fleet. The study concludes, among other things, that the more demanding Category C&D aircraft now account for 5% of jet operations, that the critical design aircraft using the Airport is now the D-II aircraft (the Gulfstream IV), and that the Airport (which has no runway safety areas), lacks sufficient runway safety areas per current FAA design guidelines for all aircraft approach categories. Additionally, the review concludes that the Airport’s geographical layout and the close proximity of runway ends to roadways and residential neighborhoods effectively preclude the construction of the traditional graded runway safety areas. Therefore, the report suggests designating runway safety areas by displacing the landing thresholds 300′ at both ends of the runway to create safety areas consistent with the Airport’s B-II designation by effectively shortening the usable runway; however this would leave the usable runway too short for C&D aircraft.

In July 2002, the safety recommendations of the Santa Monica Airport Design Standards Study are presented to the Airport Commission. In October of that year, the FAA initiates a Part 16 complaint against the City challenging “the legality of the Santa Monica Airport Commission’s apparent decision to recommend that the Santa Monica City Council adopt and implement the Airport Conformance Program”. That December the City Council unanimously approves the Conformance Program’s concept and directs staff to continue to seek a voluntary agreement with the FAA.

In November 2007, after more than five years of unsuccessful negotiations with the FAA about the Conformance Program, the City Council approves on first reading an ordinance that would promote safety and protect adjacent neighborhoods from overruns by conforming the Airport by prohibiting the generally larger, faster Category C&D aircraft from using the Airport. In March 2008, after further negotiations and Congressional intervention, both fail to yield a resolution and the City Council adopts the ordinance on second reading. The following month, the FAA issues a Cease and Desist Order and later obtains a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction from the United States District Court prohibiting the City from enforcing the Ordinance. The City appeals the decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, where the FAA eventually prevails.

In March 2009, the FAA conducts a four-day Part 16 Hearing on the validity of the City’s Ordinance banning Category C&D aircraft and later issues a decision holding that the Ordinance unreasonably and unjustly discriminates between aircraft and thereby violates the grant assurances, the Instrument of Transfer and the 1984 Agreement. This holding is based on the conclusions that the Ordinance is not reasonably justified on grounds of safety, alternative safety measures are available to the City, the Ordinance unnecessarily limits the Airport’s usefulness, and the City over-estimates its legal risks because the City could show in court that C&D usage does not create a dangerous condition. The FAA ‘s decision is made final that July so in September of the same year, the City files an appeal of the final FAA decision in the Federal Appellate Court in Washington, D.C. That Court ultimately rejects the City’s arguments and issues a narrow ruling in the FAA’s favor, based largely on the well-established principle that courts defer to agency interpretations of their own regulations. Because the D.C. Circuit concludes that the City Ordinance violates the Federal regulation prohibiting unjust discrimination, the Court finds it unnecessary to reach the issue of whether the City’s action is also preempted by Federal law.

In November 2009, a UCLA faculty member in the School of Public Health releases a study of ultra-fine particulate pollution released from jet aircraft at SMO.

Also in late 2009, the FAA begins testing a new departure heading of 250 degrees for piston-powered, instrument departures. This routes planes over portions of Ocean Park and results in protests and tens of thousands of formal complaints from residents.

In December 2010, Council directs staff to proceed with a comprehensive public process regarding the Airport’s future and authorizes hiring consultants to assist. In February 2011, Council authorizes the City Manager to commence Phase I of a three-phased process for developing possible alternatives of future roles for Santa Monica Airport within the community post 2015, with the phases consisting of initial research and surveying, extensive public workshops, and Council hearings and deliberations.

In September 2011, residents’ general complaints about the Airport and specific complaints about pattern flying connected to flight schools increase significantly after a plane piloted by a student pilot crashes into a wall in Sunset Park. In October 2011, the first phase of the ‘visioning’ process completes with the presentation of consultant reports which are widely criticized by residents as biased, superficial, and blatantly slanted in favor of aviation. The second phase of the visioning process begins and is presented in May 2012. This too serves only to aggravate the community further since its ground rules were set so as to exclude discussion of anything other than existing non-aviation land. The phase 2 report glosses over and ignores the fact that according to the comment cards filled out by attendees, over 80% of those attending want the airport mitigated or closed completely. The other 20% of attendees self identified as pilots or aviation advocates, many not from Santa Monica.

In September 2011, residents’ general complaints about the Airport and specific complaints about pattern flying connected to flight schools increase significantly after a plane piloted by a student pilot crashes into a wall in Sunset Park. In October 2011, the first phase of the ‘visioning’ process completes with the presentation of consultant reports which are widely criticized by residents as biased, superficial, and blatantly slanted in favor of aviation. The second phase of the visioning process begins and is presented in May 2012. This too serves only to aggravate the community further since its ground rules were set so as to exclude discussion of anything other than existing non-aviation land. The phase 2 report glosses over and ignores the fact that according to the comment cards filled out by attendees, over 80% of those attending want the airport mitigated or closed completely. The other 20% of attendees self identified as pilots or aviation advocates, many not from Santa Monica.

Despite rising public outrage, phase 3 of the visioning process begins, and in April 2013, staff presents the findings of all 3 phases to the Council. In a move much applauded by the community, while approving staffs recommendations, Council explicitly directs staff to: a) Continue to identify and analyze the possibilities for current and future actions to reduce Airport noise, air pollution and safety risks through Airport reconfiguration, revised leasing policies, voluntary agreements, mandatory restrictions, and all other means; and b) Continue to assess the potential risks and benefits of closing or attempting to close all or a portion of the Airport; and c) Return to Council, by March of 2014, with an assessment so that Council can determine whether the City should, after the expiration of its current obligations, implement additional changes that will reduce adverse Airport impacts and enhance the Airport’s benefit to the community or whether the City should undertake closure of all or part of the Airport.

In April 2013, in response to mounting pressure from the community to take active measures to mitigate adverse airport impacts, the Council approves a landing fee increase, effective August 1, 2013. One result of this landing fee change is to cause a dramatic and continuing drop in pattern flying (repetitive practicing of takeoffs and landings) at SMO. For the first time in decades, a concrete move to reduce adverse impacts on the surrounding community has been put in place. At the same time, the fact that even aircraft based at SMO (which were previously exempt from landing fees) must pay means that the City’s annual losses in running the airport which had historically averaged about $1 million a year, are dramatically reduced.

In August 2013, various groups opposed to the airport combine with neighborhood organizations and others to form the Airport2Park coalition. The goal of this group is to see aviation land released when SMO is fully or partially closed, turned into a great park that would more than double Santa Monica’s developed parklands and recreational facilities. The group rapidly receives endorsements from community groups across the City and surrounds.

In September 2013, a jet crashes on landing into a hanger at SMO killing 4. Community outrage at the increasing jet traffic and the dangers it represents rises to a new level, given the fact that the aircraft could just as easily have slid off the end of the runway into houses killing many more. Also in that month the City’s voluntary muffler rebate program for aircraft at SMO went into effect. This program was advocated for by CASMAT, and was designed to mitigate aircraft noise impacts through the City offering rebates for those choosing to voluntarily install approved aircraft mufflers or other noise mitigation devices. To date not a single aircraft owner at SMO has seen fit to take advantage of this opportunity to demonstrate that they care about their impact on the surrounding community.

In September 2013, a jet crashes on landing into a hanger at SMO killing 4. Community outrage at the increasing jet traffic and the dangers it represents rises to a new level, given the fact that the aircraft could just as easily have slid off the end of the runway into houses killing many more. Also in that month the City’s voluntary muffler rebate program for aircraft at SMO went into effect. This program was advocated for by CASMAT, and was designed to mitigate aircraft noise impacts through the City offering rebates for those choosing to voluntarily install approved aircraft mufflers or other noise mitigation devices. To date not a single aircraft owner at SMO has seen fit to take advantage of this opportunity to demonstrate that they care about their impact on the surrounding community.

Jet traffic has recently been increasing at a rate of 30% year-over-year so that it will reach record levels by the end of this year (2014 figure computed by linear extrapolation of published jet traffic figures from Jan-May 2014 for the entire of the year). The graph above illustrates the long term trend that played such a large part in driving community opposition. Note in particular the rapid rise in the last two years following the end of the economic downturn. If this rate continues long term, the quality of life for everyone in Santa Monica will be seriously degraded.

In October 2013, the City of Santa Monica files a lawsuit against the United States Government and the Federal Aviation Administration. The lawsuit seeks, among several things, a judicial determination of the City’s rights and options regarding its ability to plan the airport’s future.

In December 2013, UCLA researchers pitted four Los Angeles neighborhoods head-to-head to compare their air pollution levels and found that while more affluent neighborhoods generally fared better, the Mar Vista community near the Santa Monica Airport scored worse for ultra-fine particle pollutants than freeway-laced downtown and Boyle Heights and far worse than neighboring portions of West Los Angeles.

In February 2014, CASMAT reports on a strange new push-poll that seems to be testing the waters for and attempt to handcuff the City’s ability to manage the airport and mitigate impacts. They show that AOPA must be behind the poll (despite denials) by comparing it to an earlier 2011 push-poll that AOPA ultimately owned up to despite denying it at the time. This poll was clearly AOPA’s first concrete steps towards figuring out how to stop the City from regaining control of SMO land. The results from this poll were used to craft the final AOPA ballot measure and its deceptive attempt to represent itself as an anti-development measure. Also in February, a federal judge dismisses the City’s lawsuit against the FAA (following an FAA request to dismiss) on the grounds that the matter was not ripe since the City has not established to his satisfaction that there was an active ‘dispute’ to be resolved!

In February 2014, CASMAT reports on a strange new push-poll that seems to be testing the waters for and attempt to handcuff the City’s ability to manage the airport and mitigate impacts. They show that AOPA must be behind the poll (despite denials) by comparing it to an earlier 2011 push-poll that AOPA ultimately owned up to despite denying it at the time. This poll was clearly AOPA’s first concrete steps towards figuring out how to stop the City from regaining control of SMO land. The results from this poll were used to craft the final AOPA ballot measure and its deceptive attempt to represent itself as an anti-development measure. Also in February, a federal judge dismisses the City’s lawsuit against the FAA (following an FAA request to dismiss) on the grounds that the matter was not ripe since the City has not established to his satisfaction that there was an active ‘dispute’ to be resolved!

In April, the City filed an appeal on the judges dismissal of its lawsuit. That appeal is still pending.

At the March 25, 2014 City Council meeting, Council directs staff as follows:

- Consider and comment on the information provided in this report and by members of the public.

- Continue to pursue City control of the use of its Airport land.

- Direct staff to begin positioning the City for possible closure of all or part of the Santa Monica Airport (“Airport”) after July 1, 2015, including, for instance, by preparing a preliminary conceptual plan for a smaller airport that excludes the Airport’s western parcel and by preparing preliminary work plans for environmental assessment.

- Direct staff to continue to identify and undertake efforts by which the City might reduce adverse impacts of Airport operations, such as zoning the Airport land to require uses compatible with surrounding uses.

- Direct staff to increase efforts to ensure that the use of Airport leaseholds is compatible with surrounding uses.

- Revise leasing policies to maintain lease revenues so that the Airport does not again burden the General Fund by authorizing the City Manager to negotiate and execute shorter term leases for both aviation and non-aviation tenants.

- Continue to receive and assess community input on preferences and possibilities for the potential future use of the land.

- To repay the disputed grant assurance money (around $250,000) to the FAA, thereby ending the dispute over the end date of this agreement which the FAA contends extends to 2023 but which the City believes ends this year. This action also sends a clear message of intent regarding the airport’s future.

Two days later on March 27, 2014 AOPA’s (and now NBAA’s) front organization “Santa Monicans for Open and Honest Development Decisions” files notice with the City of its intent to gather signatures to place the AOPA initiative on the ballot. AOPA hires Arno Political Consultants, a firm with a long history of signature gathering fraud, to run the signature gathering effort. A small group of local residents organize to oppose the deception by turning up wherever the paid signature gatherers appear and educating the public as to what they are actually signing. The signature campaign battle escalates rapidly with gatherers routinely issuing legal threats against volunteers and calling the police on them. Many sworn statements recording election fraud and voter deception are gathered. Despite this the counter signature is very effective and ultimately forces Arno/AOPA to pay signature gatherers $20 per signature in order to meet their goals.

At this rate, gatherers from around the country descend on Santa Monica and say anything necessary to get a signature. In the mean time virtually every neighborhood organization in and around Santa Monica, as well as many other prominent political groups come out in opposition to the AOPA measure and warn their members not to sign. Significant numbers of voters who were deceived ask the City Clerk to rescind their signatures. Ultimately however, AOPA gets enough signatures after a campaign lasting nearly a month and a half. During this time a lawsuit is filed by community members to have the AOPA initiative invalidated on various grounds.

In June 2014, Christian Fry of the Airport Association (frequent source of lawsuits regarding SMO) files suit against two Santa Monica airport commissioners (and two Council members) alleging conflict of interest because they live near to the airport. Also in June the Council begins the process of drafting its own initiative to counteract the AOPA measure should it make it to the ballot.

In early July, 2014 Harrison Ford and others join AOPA and the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA – another national aviation lobby group) to file a part 16 hearing against the City in order to try to force a delay until 2023 of any attempt by the City to close down the airport.

Also in July, the Committee for Local Control of Santa Monica Airport Land is formed in order to fight the AOPA initiative at the ballot and promote the City alternative (should it be acceptable). The process of registering as a formal political committee begins. You can find a donation form for CLCSMAL here, we urge everyone to donate as much as you can afford. This will be an expensive fight (AOPA+NBAA have already spent over $1/3 million just on the signature gathering phase!).

On July 23, 2014 the City Council meeting crafts the final language for the City measure and places both it and reluctantly also the AOPA initiative on the ballot for November. Unlike the AOPA measure, the City language grants the voters a true right to vote on future development (or lack thereof) on any land released from aviation use.

Game on!

This was pretty good:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odGzWTa-HhA